SHAEF’s Strategy Prior to D-Day

Prior to D-Day, the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) provided direction to General Eisenhower, the Commander of the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), on the strategy and their intent for the prosecution of the war leading to the advance toward and eventual defeat of Nazi Germany. The core of this read: “You will enter the Continent of Europe and, in conjunction with other nations, undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.”

The Combined Chiefs’ direction and intent was codified in the 3 May 1944 SHAEF document entitled “Post-Neptune [the naval component of Operation Overlord] Courses of Action after the Capture of the Lodgment Area.” Berlin and the Ruhr the industrial heart of Germany, were identified as the most important geographic strategic objectives.

Although this directive provided great operational freedom to Eisenhower, it was clear that the CCS saw a direct relationship between the taking of geographic objectives and the destruction of the Germany military.

Command Structure for the European Campaign

General Eisenhower was appointed as the SHAEF Supreme Commander on 24 December 1943. British General Bernard Montgomery was placed in command of the Allied land forces initially comprised of the British Second Army under Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey and the US First Army led by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley. After the Allied forces were well established ashore and in preparation for the breakout from Normandy, these armies were reinforced by Lieutenant General H.D.G. Crerar’s Canadian First Army, which joined the British Second Army in Montgomery’s newly activated British 21st Army Group, and Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr.’s US Third Army, which together with the US First Army comprised the newly activated US 12th Army Group under Lieutenant General Bradley. In August 1944, Lieutenant General Alexander Patch’s US Seventh Army landed in southern France, advanced north, and established contact with Patton’s army. Soon reinforced by General de Lattre de Tassigny’s French First Army, the US Sixth Army Group was formed under General Jacob L. Devers.

At this point, Montgomery as the Land Forces Commander remained in command of both army groups, thereby having both strategic and operational responsibilities. However, on 1 September 1944, Eisenhower assumed the position of Land Forces Commander in addition to his responsibilities as the theater commander, thereby centralizing strategic control over all three Allied army groups. This was unanticipated by Montgomery, who was now limited to operational level matters associated with only his army group. Despite his compensatory promotion to Field Marshal, Montgomery would spend the rest of the war seeking to recover command of the Allied land forces.

Eisenhower’s Strategy for the Campaign

Undoubtably, Eisenhower was the master of coalition warfare and this was his greatest contribution to victory in the (European Theater of Operations) ETO. His mentor, General Fox Connor (who had served as the Operations Officer for the American Expeditionary Force in the Great War and after retirement continued to mentor other promising officers) and Ike’s study of Clausewitz had instilled in him the need to focus all combat power on the enemy’s center of gravity. This was defined by the CCS as the heart of Germany and her armed forces: Eisenhower’s goal was to destroy and replace the Nazi regime. His responsibility was to determine how best to achieve this.

Eisenhower believed that sequenced, coordinated attacks along multiple axes of advance kept the enemy off-balance and unable to concentrate against any single blow. As the war progressed, Eisenhower increasingly relied upon geography to entrap and destroy the enemy west of the Rhine so that the Allied crossing of that mighty waterway would face much less resistance. His geographic objectives were the immense Ruhr industrial region immediately east of the Rhine and the smaller, but still important, Saar industrial region to the south along the French border. Together, these two regions underpinned the bulk of the German military industrial might. By picking this strategic course of action combining geographic objectives and enemy military strength, Eisenhower was fully responsive to the CCS directive.

The Supreme Commander understood that the US Army would continue to grow in strength and, in the near future, would overshadow the British Army in size, sustainability, and combat power. (By the end of the war in Europe, the US Army forces there outnumbered the British 21st Army Group by about three to one.) This meant that the US, rather than Britain, would play the decisive role in defeating Germany. Furthermore, certainly no other American field commander had Eisenhower’s depth of experience on Allied grand strategy, maintaining Allied relationships, and the relationship between military operations and higher political matters. But he also understood that, while he could direct his Allied subordinates, he had to be judicious in issuing orders to them and even more so in enforcing those orders.

Possible Axes of Advance to Germany There were five possible axes of advance from France and the Low Countries to Germany.

The Flanders Plain through northern Belgium and southern Holland was ideal for maneuver as it was flat, crossed by an extensive road and rail network, and also offered numerous airfields. However, major waterways (the Meuse/Maas, Waal, and Rhine Rivers), canals wide and narrow, and countless smaller rivers crossed this path. For these reasons, as well as the extensive German coastal defenses and the West Wall fortified line that also blocked this path, the SHAEF planners rejected this axis.

To the south, the Maubeuge-Liège-Brussels-Maastricht-Cologne axis crossed many fewer waterways, and also offered mostly flat terrain with good road and rail networks, and prospective sites for airfields. Obstacles here included the West Wall, the heavily forested and fortified sector of Aachen and many other urban areas that would impede movement. However, this axis provided the shortest path of advance (about 125 miles/200 kilometers) to the Ruhr. This axis also was within distance of medium bomber airfields in England, and also the troop carriers that could deliver the Allied First Airborne Army. However, Berlin was still about 360 miles/575 kilometers distant from Cologne.

The next two axes of advance were even less attractive. Immediately to the south of the Maubeuge-Cologne axis was the mountainous and heavily forested Ardennes and Eifel region of Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. The rough terrain here crossed many small, yet tactically significant waterways and the limited road network provided the German defenders great advantages. Furthermore, the West Wall also protected it. Given this, SHAEF preferred moving around the Ardennes rather than through it.

The Metz-Kaiserslautern Gap on the right of the Maubeuge-Cologne also was characterized by forests and heavily compartmented terrain. However, if the French cities of Nancy in the south and heavily fortified Metz in the north were taken, access to an adequate road network was possible. Unfortunately, this part of the German border was lined with some of the strongest fortifications of the West Wall. Also, the Meuse and Moselle Rivers were formidable obstacles easily held by the defender. This path led to the Saar industrial area, beyond which difficult terrain made approaching the Rhine difficult.

The fifth axis led northeast from central France and north from southern France. However, there were no industrial centers or other strategic objectives, and Berlin was a very distant 430 miles/700 kilometers away. The US Sixth Army Group would advance here from the Mediterranean coast to eventually link-up with the main Allied thrusts from Normandy across France and the Low Countries.

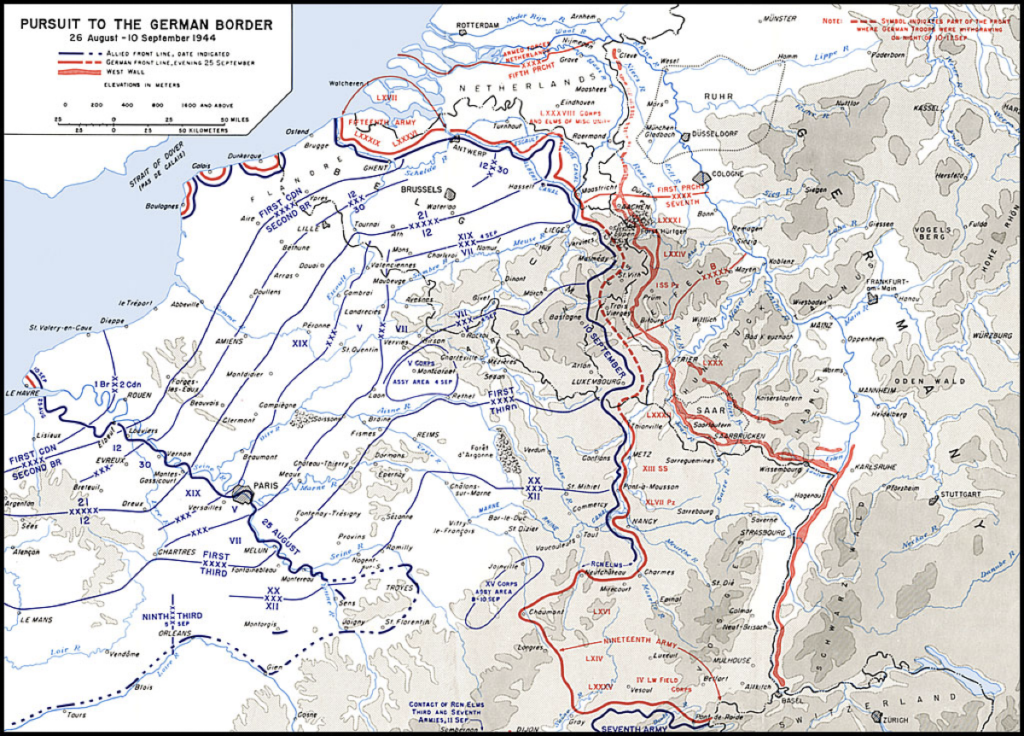

The SHAEF Strategy Eisenhower decided long before the invasion of France to make the advance toward Germany on a broad front. This offered the advantages inherent in employing multiple avenues of advance to keep the enemy off-balance and unable to mass his strength against a single thrust. The main advance was to be directed to the northeast, north of the dense Ardennes Forest, with the objective being the massive Ruhr industrial region. This was the objective of the British 21st Army Group. A subsidiary effort was to be made south of the Ardennes by the US First Army toward Metz in France and the smaller German industrial center of the Saar. All other remaining Allied advances were intended to protect the right (south) flank of these two main efforts.

However, this strategy faced three challenges. First, the Allied victory in Normandy resulted in the pursuit of a defeated enemy who saw no safety short of the West Wall along the German border. Originally, SHAEF anticipated that the advance would reach the Seine River by the end of August or early September. Here, a month-long pause would be made to improve the logistical state of the armies and reorganize for the advance. Instead, the Allies had shattered the German armies in the West, unexpectedly creating a fleeting opportunity to destroy whatever enemy forces remained, followed by the rapid advance into the heart of Germany.

The second challenge was driven by the logistics — the science of planning and carrying out the movement and maintenance of forces. The initial post-Normandy plan called for a three-stage offensive with each one providing ports for achieving the next stage. The first phase, based on the artificial “Mulberry” ports constructed by the Allies off the D-Day beaches, the damaged but repaired port of Cherbourg, and smaller Normandy ports, was expected to last a few weeks.

It was anticipated that the second phase would span July into August. This ambitious phase added the liberated ports of Brittany, of which Brest being the most important; extensive repair of the French rail network; and the installation of oil pipelines. The result of this would be the establishment of a massive supply and support base area between the Seine and Loire Rivers. Offensive operations would be minimized during this period and resumed on or about D+120 days. Expected gains during the renewed offensive included the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam located near the Germany border, which would sustain the advance until victory was achieved.

Cherbourg, smaller Normandy ports, the single fully functional Mulberry, and over-the-beach delivery had provided for adequate sustainment of much of the Allied force so far. However, in the absence of anticipated forward supply and support base areas, and with insufficient time to repair the rail network, ad hoc means had to be found to sustain any advance. This placed great reliance upon trucks operating over ever-increasing distances — a most inefficient means of sustaining a rapid advance. With both Montgomery and Bradley insisting that he be given the greater share of supply at the cost of the other, allocation of what could be delivered became the most highly divisive factor in Allied planning and operations throughout most of the remainder of 1944.

The third challenge was that the German V-1 “flying bombs” being launched from the French Pas-de-Calais region and the Netherlands were having significant material and morale impacts in England. This area had to be cleared, but was held by the largely intact German Fifteenth Army which had not yet been engaged in ground combat.

A Change in Priorities On 23 August 1944, Eisenhower proposed to Bradley and Montgomery that the 21st Army Group shift the weight of its advance somewhat more toward the Flanders Plain and the Channel Ports to address the latter two challenges. Field Marshal Montgomery was receptive to this with the proviso that the US First Army shift its advance north of the Ardennes to protect his right flank. Eisenhower agreed to this as it remained in accord with the earlier decision of advancing to the north of the Ardennes. Thus this meeting resulted in a temporary shift of the main advance from the Maubeuge-Liège-Aachen to the Flanders Plain. However, it meant that rather than the US 12th Army attacking north of the Ardennes with both of its armies, its two armies would be separated by the Ardennes.

Further complicating the situation was that Montgomery then proposed that his mission be broadened into the main effort, backed by the full weight of the Allies, in an advance to and over the Rhine, followed by a single powerful thrust into the heart of Germany. Eisenhower nixed the idea on the bases of vulnerability of a deep narrow thrust to counterattack along its extended flank and leaving other sectors of the front lightly held and vulnerable to enemy attack.

Eisenhower would never fundamentally change his strategy, despite endless pressure to do so from Montgomery and, to a much lesser extent, from Patton who believed that, if his Third Army was fully supplied, he could race to the Rhine, “jump” that river, and continue deep into Germany.

Montgomery— Personality and Experience

Montgomery’s difficult personality traits are well known. He was arrogant and rude, unable to work well with others, and had supreme confidence in his abilities as a combat commander. He did not welcome visitors — even more senior officers and civilian officials — to his private headquarters. The only senior officer he ever respected was British Field Marshal Alan Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, who was Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the professional head of the British Army and Montgomery’s superior officer, during the Second World War. Unless Field Marshal Alanbrooke was attending, Montgomery usually declined to attend SHAEF briefings, claiming that operational demands prevented his leaving his command post. Otherwise, his primary representative to Eisenhower was his Chief of Staff (CoS), Major General Freddie de Guingand. This was an obvious snub of Eisenhower, whom Montgomery considered to be an amateur at war.

Montgomery thought of the British 21st Army Group as his personal property and maintained a close hold on it operations. In simple terms, he wanted to left alone to fight the war his way. It’s impossible to like Montgomery and very difficult to be fair in assessing his skill as a combat leader.

The Professional Soldier To his great credit, Montgomery — unlike most British Army professionals of the 1930s — was a serious student of war and saw the 1914-18 War not as an aberration in the practice of war, but rather a forecast of future wars. He was an excellent trainer of troops, knew how to build and maintain morale, understood and advanced the coordination of ground forces and tactical air support, and based on his Great War experience, strove to never waste the lives of his troops for no good reason.

In the 1930s, Great Britain, like most major powers, struggled with the role of tanks in warfare. As an infantryman, Montgomery thought of armor as best suited for the exploitation of breakthroughs achieved by the infantry and artillery. However, the experience of the Great War revealed that the infantry needed the mobile, protected firepower provided by tanks to achieve a decisive breakthrough. This led the British to develop three distinct types of armor formations: “tank regiments” for infantry support, “armoured regiments” with tanks designed for exploitation of breakthroughs and engaging enemy armor, and reconnaissance regiments with light, fast tanks to collect information on enemy forces and battlefield conditions.

Early WWII Accomplishments Montgomery commanded the 3rd Infantry Division during the 1940 German Blitzkrieg across France. Following the Dunkirk evacuation, his command retained high morale, good cohesion, and was selected as the first division to be rebuilt and positioned to counter the expected German invasion of England. From there he assumed higher responsibilities at the corps level. Eventually placed in command of the Eighth Army in Egypt, he defeated the vaunted Afrika Korps led by General (late Field Marshal) Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox” in a set-piece battle. But when the infantry failed to achieve the breakthrough, Montgomery had to commit his armor to break the German defense. However, Montgomery proved slow and cautious in following his retreated foe, who escaped to fight another day. El Alamein was only the first time that he failed to convert a battle won into a much more decisive victory. Yet, beginning in North Africa, he made good progress in improving the coordination of all arms — tanks, infantry, artillery, and air support — in battle. His efforts would continue following a disappointing performance in the weeks after D-Day, but soon after that they resulted in a highly effective battlefield performance for the remainder of the war.

The Lack of the “Killer Instinct” Placed in charge of the Allied invasion of Sicily, Montgomery’s performance again showed a predilection for methodical planning and cautious operations, that allowed the German defenders to efficiently and safely withdraw from the island to the Italian mainland despite the Allies having complete control of the seas and skies. This was Montgomery’s second demonstration of the lack of a killer instinct. He would miss three additional opportunities later in the war — in Normandy where a large part of the German army and most of its leadership was able to escape when the Allied trap at Falaise failed to be properly closed. During the advance of the 21st Army Group toward the Low Countries, the German Fifteenth Army escaped intact and later played a key role in the defeat of Montgomery’s Operation Market-Garden. When he was placed in command of the Allied forces (overwhelmingly Americans) on the north flank of the German break-in during the Battle of the Bulge, Montgomery played it safe, squeezing the enemy out of the Bulge rather than acting on the advice of his American subordinates to cut off the enemy by attacking north and south at the base of the German penetration. A case can be made that Montgomery thereby missed a fifth opportunity in his career to destroy a defeated and retreating German army.

Montgomery at the Strategic and Operational Levels

When Montgomery was appointed to command the D-Day invasion, he inherited a plan that pre-dated both his and Eisenhower’s arrivals in England. Montgomery correctly deemed the landing zone as far too small in size, in depth, and breadth, that would probably lead to failure. Eisenhower strongly agreed and the landing zone was increased from three to five beaches upon which six complete American, British, and one Canadian divisions would land on D-Day. In addition, two American airborne divisions supported the landing on westernmost Utah Beach and a British airborne division established a bridgehead on the eastern flank of the invasion area east of the Orne River. Despite difficulties on several landing beaches, most notably by the US V Corps at Omaha Beach, and the failure of the American airborne divisions to secure all of their objectives, D-Day proved to be a great victory at lower cost than anticipated.

Once the beachhead was secured, the next imperative was to increase its size to provide sufficient room for the buildup of men, material, and supplies to breakout of the lodgment area and begin the advance toward Germany. This proved very difficult as the Germans had moved up strong armored forces to block the British Second Army on the more open terrain of its eastern zone, and maximized the use of the dense Normandy hedgerows to greatly limit British and American advances in the western part of the lodgment area.

There were good reasons for this lack of progress, the first being a tenacious and experienced foe. Both Allied armies contained a mix of experienced and inexperienced divisions; the former, especially in the case of the British were war-weary and tired, and the latter went through the inevitable steep learning curve of warfare. Bad weather also prevented the planned buildup of resources for the breakout as well as the employment of airpower. The heavily compartmented terrain of the Normandy battlefield also taxed the capabilities of both the American and British armies, and largely negated their great advantages in mobility and air power.

After Normandy, Montgomery doubled-down on his methodical and cautious approach to war, which, although it mystified his Allies, was the right course of action from the British perspective. Why and how Montgomery fought in such a manner will be subject of the next posting.

Enduring Challenges

The Allies faced serious challenges throughout the remainder of 1944.

Irreconcilable Differences Eisenhower and Montgomery had irreconcilable differences regarding the relationship between, and the prioritization of, seizing geographic objectives and destroying the German armed forces. Following the conclusion of the Normandy Campaign, in which the Allies missed an opportunity to achieve a near total destruction of the German army in the west, Eisenhower more so than Montgomery, focused upon destroying Wehrmacht, preferably by pinning him down in defense of vital geographic objectives such as the Ruhr. The escape of the German 15th Army along the Channel coast was the fourth time in which Montgomery failed to destroy a retreating highly vulnerable German army. The priority Eisenhower placed upon destroying enemy forces west of the Rhine was intended to deny the Germans the strength to make a strong stand along that river, the last barrier before entering the heart of Germany. Eisenhower was also among the first to grasp the opportunity to accomplish this when the Germans launched their counteroffensive in the Ardennes in December 1944.

The Tyranny of Logistics Logistics would continue to plague Allied strategy and operations through the opening of the port of Antwerp in November 1944. Until then, only Cherbourg — some 450 miles/720 kilometers from the British front lines on 5 September and 400 miles/645 kilometers from the front of the US Third Army — was capable of receiving supplies in the quantity needed. The greater challenge remained moving these supplies to the front.

Allied Manpower Limitations While a steady flow of American divisions and massive combat service and support elements continued to arrive in theater, the British faced severe manpower shortages, particularly in their infantry formations. The cause of this was five years of war in which Britain suffered heavy losses on battlefields around the world, compounded by a great Allied underestimation of actual infantry casualties experienced on the battlefields. Although the US could replace its infantry losses (not without difficulty), the British could not. Toward the end of the Normandy campaign, Montgomery quietly broke up the first of what would eventually prove to be several infantry divisions to provide replacements for other such formations.

Montgomery chose to conceal his worsening manpower problems from his Allies despite it being the major factor in determining the form and conduct of the British 21st Army Group’s operations for the remainder the campaign. No doubt Montgomery and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff believed that talking openly about their manpower issues would result in SHAEF limiting the role of the 21st Army Group in winning the war, as well as Britain’s ability to win the peace that would follow.

Concluding Remarks

Next, we will look in detail at the features of the British operational doctrine, which Montgomery described as being the concentration of great force “to hit the Germans a colossal crack.”