An earlier blog posting addressed the mission of the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), which manages and operates American overseas military cemeteries, including the ten in what was the European Theater of Operations and the three in the what was the Mediterranean Theater. This blog also addressed how to plan for a memorable visit to one of these cemeteries, what to expect during a visit, and our favorite memories of visits to seven of them across France, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

The Volksbund

The German counterpart to the ABMC is the “Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge,” the German War Graves Welfare Organization, founded in 1956 to “guard the memory of the victims of war and violence, to work for peace among all nations and to guarantee dignity of men.” Like the ABMC, this organization maintains the war cemeteries and memorials to the German dead from the First and Second World Wars. In all, the German Commission cares for 832 cemeteries in 46 countries, with more than 2.7 million graves of known and unknown German soldiers and civilians. Many German war dead are also buried in cemeteries maintained by the British Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). In addition, the Volksbund maintains cemeteries and memorials of the Franco-Prussian War, First and Second Schleswig Wars, and the German colonial era. It also maintains online data bases of 4.8 million individual names from the World Wars and organizes subsidized pilgrimages for families.

Two-thirds of its budget comes from members and private donations. The remaining one-third is provided by the German federal and state governments, primarily for the maintenance of war graves outside and inside Germany, respectively.

Ongoing Recovery of War Dead

Although the remains of Allied war dead occasionally are still found, the focus is now largely on identifying the unknown burials. However, the Volksbund is actively searching for war casualties and, when found, transfers them to central cemeteries in Eastern Europe, Germany, and Western Europe. There were 19,735 exhumations in the year 2019 with remains being interred in these cemeteries.

Reconciliation

On our early visits to Europe we noticed that the German war cemeteries flew only the Volksbund flag (five white crosses on a light blue background). There was no Federal Republic of Germany or French flag present. However, several years later we noticed that the French and German flags were flying at all German war cemeteries.

A Different Kind of Experience

We have visited dozens of small and large German war cemeteries across France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the German Rhineland. Little detailed information in English is available and we never quite know what to expect at each cemetery. Maps mark the location of all German war cemeteries, but sometimes until we arrived we had no idea on whether we were going to find graves from the First or Second World War, or both. The following are some of our experiences at German war cemeteries.

* La Cambe, Normandy — How does an invaded and occupied country deal with the burial of enemy dead on its soil? This is obviously a very emotional question. On our first visit to France in 1999, we visited two of the six German cemeteries there. The largest of the Normandy cemeteries, La Cambe, is located along the major highway from Caen to Cherbourg and close to the major D-Day sites. Originally a wartime cemetery for both US and German war dead, La Cambe represents the “high end” of the German war cemetery: visible and accessible, large (21,222 graves) well-designed and maintained, and hosting large numbers of visitors of all nationalities every day. We have since visited here several more times. On every visit (most recently in 2019) we noted that the grave of SS-Hauptsturmführer Michael Wittmann (Block 47, Grave 3, 121F), a top-scoring tank commander of WWII best known for his defeat of a British armored column at Villers-Bocage on 13 July 1944, was marked by flowers and a burning candle. We have no idea who continues to honor Wittman in this manner and why. However, like all German war cemeteries, the intended impression on visitors is one of sadness and a desire to avoid future wars.

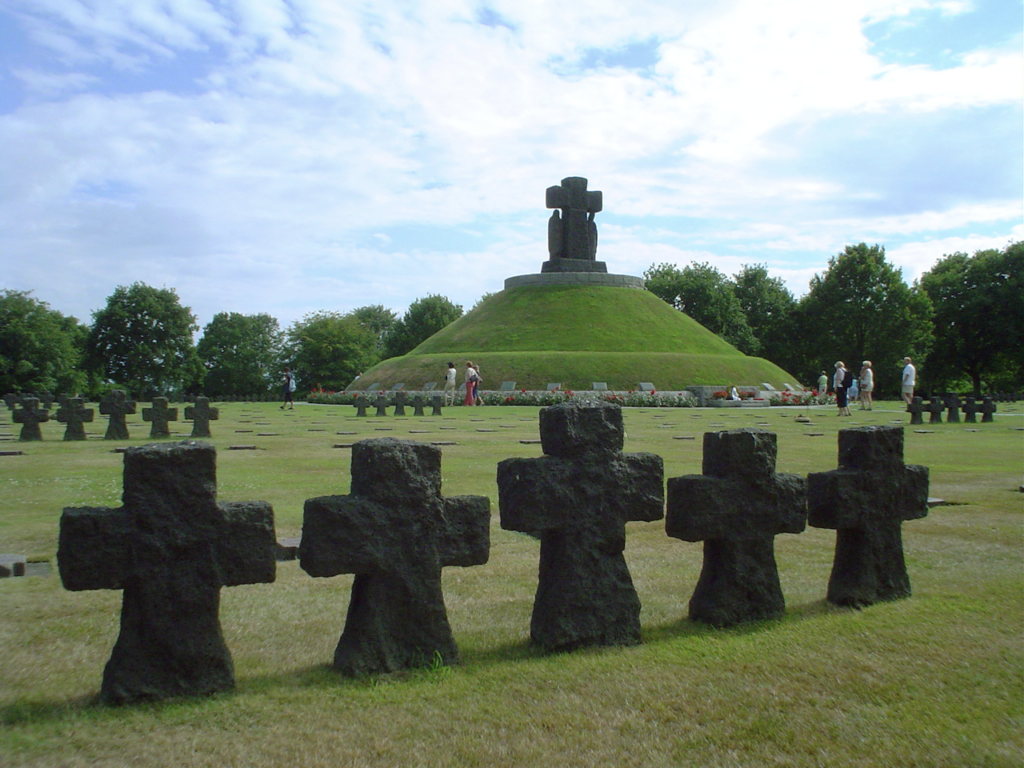

Below: La Cambe German War Cemetery, Normandy France — The mound is a mass grave for 296 German soldiers, Each side of the headstones list two known or unknown soldiers.

* Marigny-le-Chapelle, Normandy — Located deep in the Normandy bocage, the Marigny cemetery is much smaller, yet still massive with 11,169 burials. A bit off the beaten paths, it is far less visited with never more than a handful of other visitors while we were present. Nonetheless, it is still well-maintained, which is rarely the case for most such hidden away and largely forgotten war cemeteries.

* Lommel, Belgium — With over 39,000 graves, this is the largest German military cemetery in Western Europe outside Germany. Lommel was our first and still most depressingly memorable experience of the type of dark and somber cemeteries we increasingly encountered as our trips moved us closer to Germany. There were few visitors when we arrived, but rock music was blasting from the German Youth Camp here where students were spending the summer. Listening to that while gazing across graves extending out to the horizon and beyond was a very strange experience. The youth camp here dates to the 1953 construction of the cemetery and consolidation of graves from other cemeteries mainly across Belgium and the teenagers worked under the slogan “Reconciliation over the Graves.” They now help mainain the cemetery and learn about the war under a new slogan of “Work for Peace.” Undoubtedly, the most depressing features of this cemetery (and others) were dark statues in the crypt-like rooms.

Below — The entrance to the Lommel German War Cemetery in Belgium and the view from the top of this structure.

* Bourdon German War Cemetery, France — One statue we particularly remember was at the Bourdon German War Cemetery near the River Somme in 2010. The cemetery contains 22,213 Germans killed during the 1940 fighting as well as the battles that occurred when the British 21st Army Group fought its way along the coast toward Belgium in August and September 1944. Passing through the cemetery’s medieval-like round tower and down a long, dimly-lit corridor, we entered a chamber containing a large statue of a painfully mourning woman, a work by the sculptor Professor Gerhard Marcks entitled “Mother.” Visitors had left photos of uniformed German soldiers around the statue’s base; however, unlike British and American cemeteries, these photos did not include names or family histories. It was as if the visitors wanted to remain anonymous. Adding to the prison-like appearance odf the chamber were two heavy steel doors — like those at the entrance to a bomb shelter — that opened to the cemetery grounds.

* Ehrenfriedhof Vossenack, Germany — This is one of six German war cemeteries in the Hürtgen Forest. Unlike the previously mentioned cemeteries, this one is maintained by the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. This is also the final resting place of Field Marshall Walter Model, at grave 1074 near a line of crosses. Model was noted for his performance in the latter half of the war, mostly on the Eastern Front. Although he was a hard-driving, aggressive panzer commander early in the war, Model became best known as a practitioner of defensive warfare. In April 1945, Model was trapped with the German forces in the Ruhr and committed suicide rather than be captured.

Unfortunately, the photo below is more representative of the countless smaller, isolated German war cemeteries across France and Germany. Given the large number of such cemeteries across Europe, the maintenance cost must be high. The victors in the war are more than willing to bear this price so that relatives and the coming generations can appreciate the sacrifice of those lost in the war. Regardless of the size and location of American, British, Canadian, and Polish war cemeteries, all are equally well maintained. That is clearly not the case for German war cemeteries. We have stumbled upon some literally hidden behind berms or inside deep woods. Often, the worn headstones contain only a name and date of death — far less information than that found on graves of Allied war dead. Why some German war cemeteries remain well cared for while others are abandoned is unclear. We have often wondered how the descendants of the German war dead feel about this.